Anthropology of Smartphones: Exploring Ecologies

It might seem obvious to consider the smartphone primarily as an app machine, but actually, an alternative perspective might work better. Similarly, it would seem obvious that the best way to study smartphones is to focus upon the relationship between an individual and their particular smartphone. In this article, we will suggest reasons for favouring an alternative approach.

What is ‘screen ecology’?

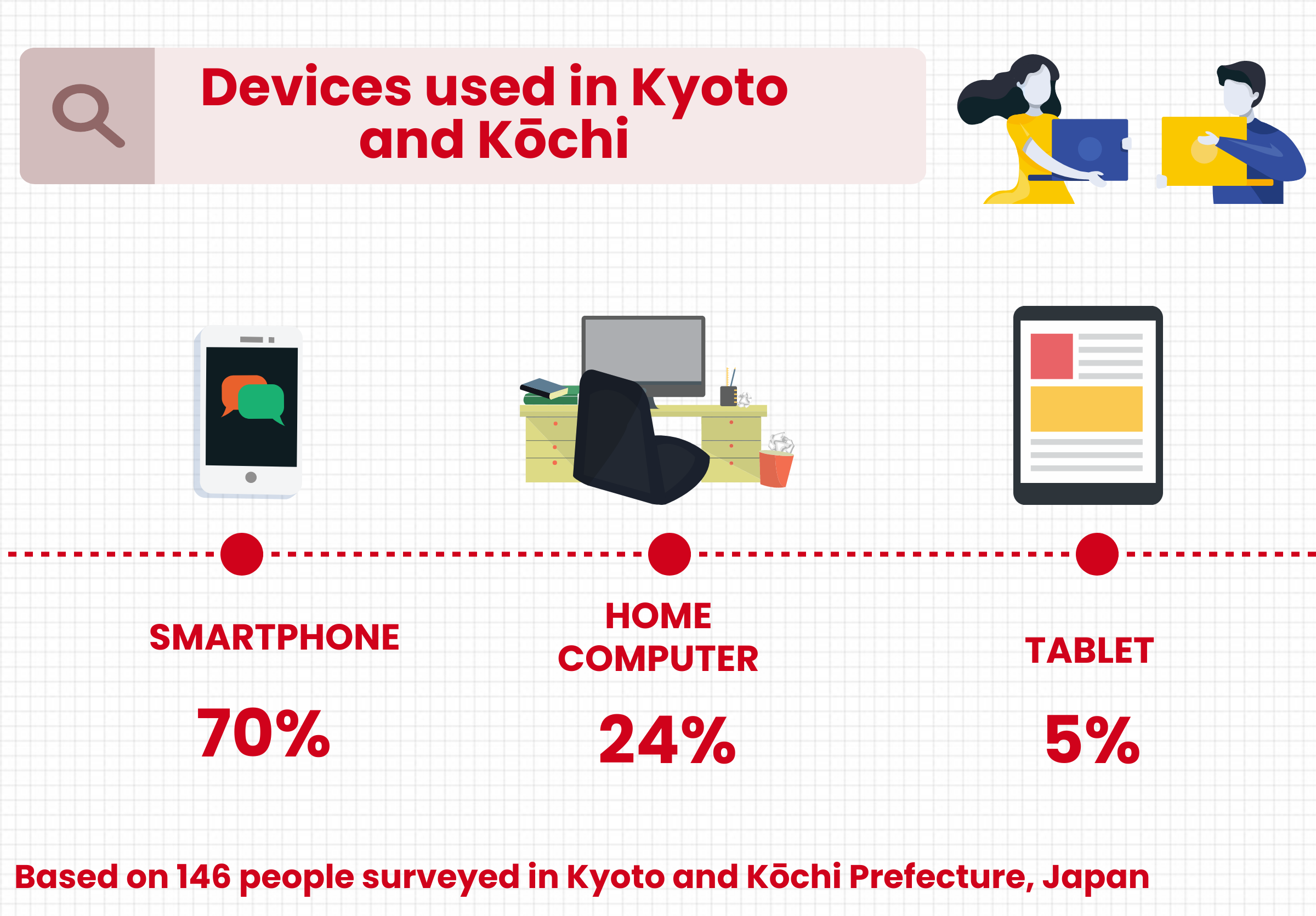

The term ‘screen ecology’ is defined as the relationship between the smartphone and other screen-based devices, such as televisions, tablets or laptops. In most fieldsites, people have access to a variety of devices through which they can access the internet, as shown by the infographics below, based on research from Laura Haapio-Kirk and Shireen Walton.

What is ‘social ecology’?

The term ‘social ecology’ is defined as the social relationships that follow from the sharing of smartphones and apps. Just as smartphones only make sense when looked at in relation to other screens, their owners also need to be considered in relation to other people, whether we are talking about family relations or the workplace.

An example of social ecology comes from Lusozi, our fieldsite in Uganda, where it is common for a smartphone to be shared by several people. Nakito (seen in the photo below), who runs a hair salon together with her son, shares a smartphone with him to cut down on costs. They both take turns as the main phone holder, updating the phone’s password and background photo. That way, both of them have periods of independent ownership but can also use the phone at any time with permission from the current owner.

Domestic arrangements and seeing the multi-screen picture

In some other places, domestic arrangements are critical to understanding smartphone usage. In the Dublin fieldsites, there were several cases where a wife had the apps that reflect her emphasis upon maintaining social connections, while her husband had the banking and technology apps. In São Paulo, it was often the other way around. There are also close elderly couples in Shanghai, where only one of the partners has an individual app on their smartphone since both partners happily pick up whichever smartphone is nearest, all of which gives an insight into why methods such as surveys that rely on the self-reported data given by individual research participants might only show part of the picture.

When it comes to screen ecology, we found that there was great variety in how people used their different screens: we came across participants whose primary device was the iPad, and who only used their smartphones to complement it. Others preferred to do certain tasks on their laptop. In Japan, a research participant held on to her old feature phone in order to keep certain memories and contacts long after she had purchased a smartphone. Very common today are people who try and do more things through the smartphone but have niches of activity such as creative writing that they use larger screens for. So again, we cannot understand what is or is not on a smartphone unless we see the bigger multi-screen picture. One person may access TripAdvisor through an app, while another only ever accesses TripAdvisor through a website. It was only because we spent our time focusing on detailed stories rather than listing what we could see, that all this complexity made itself apparent.

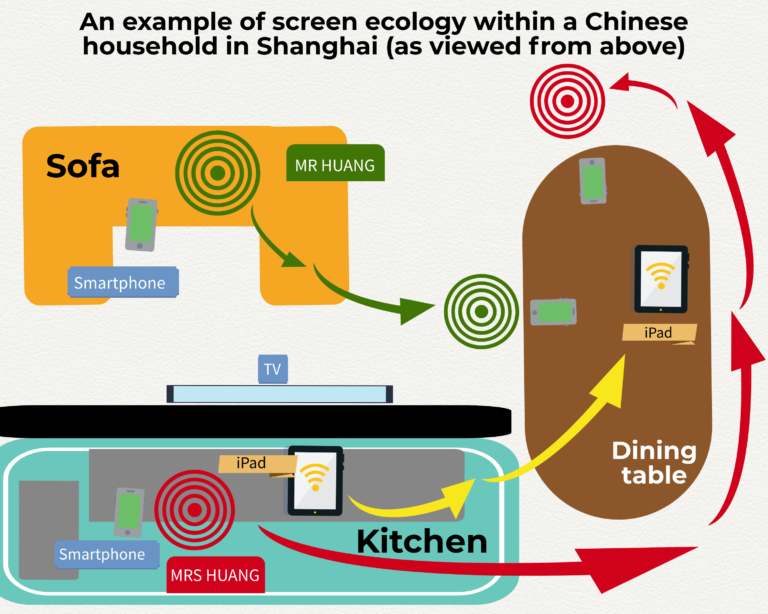

In practice, ‘screen ecology’ and ‘social ecology’ go together, as you can see in the following extended case study from Shanghai, which depicts the Huang household.

A case study of the Huang household

Mrs Huang is checking the weather ahead of planning a trip, while for the same reason, her husband is using the Gao De app (a Chinese mapping and navigation app) to plan their route. Then, the couple hear the iPad ring – it is Xiaotao, their grandson living in Beijing, where their son-in-law works.

The Huangs see their daughter and her family every three months but have video calls with them much more often. Mrs Huang fetches the iPad and places it on the dining table, so they can speak. From time to time, Mr Huang takes photos of Mrs Huang happily talking with Xiaotao and then sends them to the family WeChat group. While they are still talking, Xiaotao’s Nainai (the child’s grandmother on his father’s side) has replied to these photos with WeChat cute stickers saying ‘nice shot’. Since she was visiting Xiaotao, she can then post photos of the video call from the other end. Mrs Huang in turn shares the photos with her WeChat group ‘Sisters’, which includes her three close female friends.

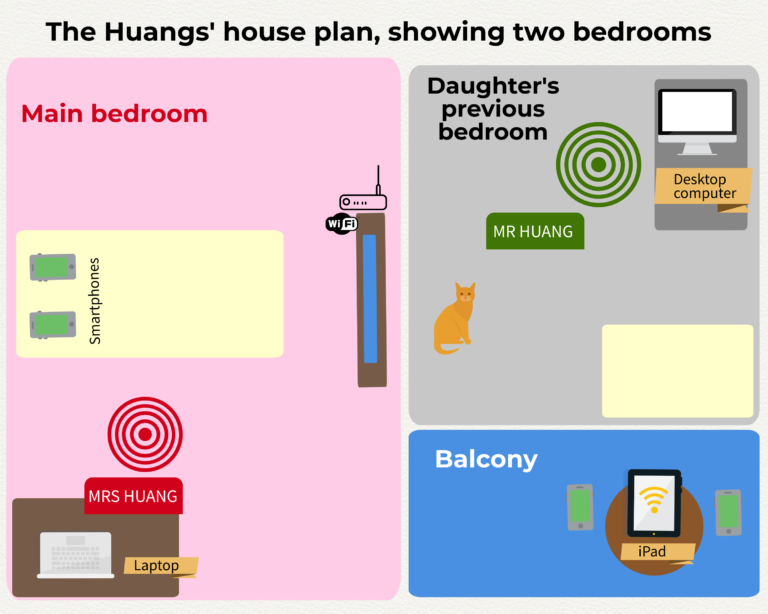

There is nothing exceptional about this dinner scenario. It involved at least eight screens in three locations within a single hour, with the images supporting moments of intergenerational bonding for a retired couple. Below are two visual illustrations of the couple’s movements around their various screens, which reveals how they simultaneously reinforce the sense of their domestic surroundings, as well as incorporating more distant kin.

In the past, placing family photographs around the rooms would have served the same purpose; now, thanks to these screens, it feels like those images have come alive. This domestic ‘screen ecology’ is quite sophisticated. The bedroom in the image above includes another television, along with a laptop and desktop computer inherited from their daughter and used mainly by Mr Huang, but also a place to nap for their cat. In the early afternoon, if it is a nice day, the couple will sit on the balcony for a cup of tea, each of them on their own smartphone. The iPad means that Mrs Huang can either watch soap operas there or take the device into the kitchen to continue watching while she cooks. Cooking also involves making use of the ‘Go to Kitchen’ (Xia Chu Fang) app for her video illustrated recipes and iQiyi – one of the largest online video sites in the world, used for six billion hours each month and often dubbed ‘the Netflix of China’.

This case study also indicates the relationship between the family and the ‘transportal home’. The smartphone, along with other screens, is being used as a portal that allows the households of extended family members to appear as though they were now within this household. So ‘screen ecology’ and ‘social ecology’ can have important consequences for the everyday life of the family.

What about your own experiences?

Is there, for example, an app you don’t have on your phone because another member of your family tends to carry out that task, or a task you could carry out on your smartphone but prefer to use an alternative device? Or is there another member of your family who does certain things on their smartphones, as a result of which you tend not to do those things on your smartphone?

Are there some tasks you tend not to do on your smartphone because you prefer to use another device?

An Anthropology of Smartphones: Communication, Ageing and Health

An Anthropology of Smartphones: Communication, Ageing and Health

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free