Sanitation in peri-urban areas

With an ever-increasing number of people living in urban areas globally, cities and their surroundings, especially in low- and middle-income countries, are facing increasing challenges to meet the demand for basic needs services, such as housing, food and water, education, healthcare, and sanitation services.

Innovative, non-traditional approaches are needed to cope with the challenges resulting from rapid urbanisation and population growth in the water and sanitation sector.

What are peri-urban areas?

According to the United Nations, it is expected that by 2050 two thirds of the world’s population will be living in urban areas – this is nearly one billion people more than now. With this increased pressure on already rapidly growing urban centres, there will be an inevitable expansion of the urban fringe into the rural surroundings outside the formal city limits.

This overtaking of rural land traditionally associated with agricultural and recreational land use creates so called peri-urban areas with mixed, and sometimes competing, usage patterns.

What are the challenges?

For example, in India, less than 20% of the total waste water generated is actually treated.

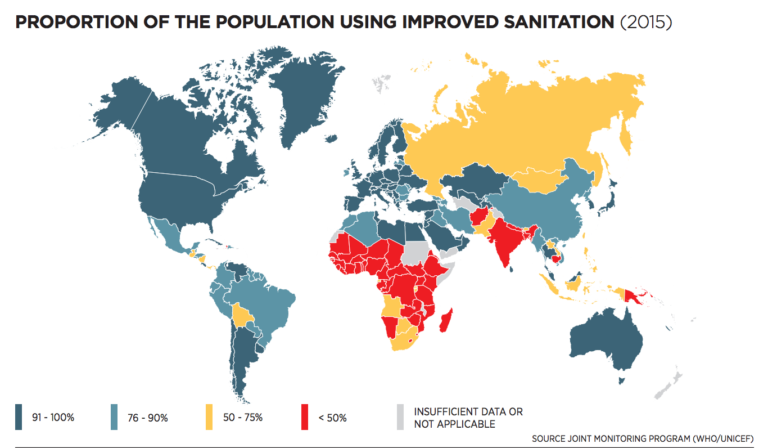

Global access to improved sanitation. Source / Click here to enlarge

Global access to improved sanitation. Source / Click here to enlarge

Traditional approaches essentially focus on large-scale centralised systems under municipal oversight, carrying high cost of investment and for underground transport in extensive sewer networks. Because of the long implementation phase and lack of flexibility, those approaches are not the most suitable for rapidly growing peri-urban settings.

What are potential solutions?

Especially in the peri-urban context, decentralised approaches offer a more flexible strategy and have been adopted across many different regions that are under-served by centralised networks. The implementation of onsite and decentralised cluster treatment systems is, generally speaking, less resource intensive, and more adaptable to local conditions. Wherever possible, their design is guided by the idea of creating low-maintenance, natural treatment systems without the need for energy inputs or the use of technical equipment.

However, in order to achieve SDG 6, sanitation interventions should not only rely on technical improvements on the infrastructure, but also address procedural and behavioural changes in the community. Integrated approaches including capacity building and education in proper sanitation and hygiene practices are needed, regulations and guidelines have to be drafted, and professional operation and maintenance procedures be devised to be able to scale decentralised solutions adequately.

You can have a look at how community-led initiatives take on holistic approaches to collaborative sanitation solutions in Indian villages in Joe Madiath’s passionate TED talk in this video.

The sanitation value chain

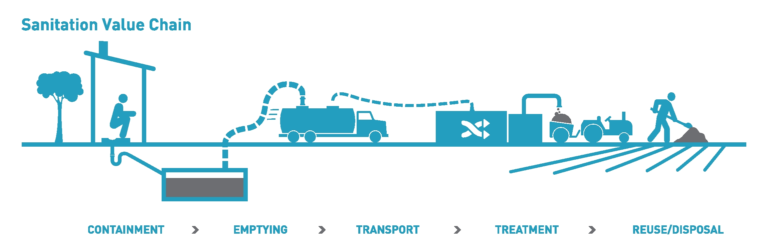

Yet, in order to improve overall sanitation levels in urban and peri-urban areas, the whole sanitation value chain has to be taken into consideration. According to the WHO, a staggering 946 million people worldwide still defecate outdoors; it is not enough to only provide toilets and basic sanitation infrastructure. Proper collection and storage of human waste, its conveyance to an adequate treatment facility, and the need for local resource reuse and final disposal are equally important factors in building a sustainable sanitation infrastructure.

The sanitation value chain (source: SuSanA Secretariat on Flickr)

The sanitation value chain (source: SuSanA Secretariat on Flickr)

So-called Sanitation Safety Plans (SSPs) provide a structured set of tools to identify and manage health risks associated with the use of human waste. Developed by the WHO in 2010, they particularly focus on sharing roles and responsibilities among different sectors and stakeholders, e.g. from local authorities to utility operators, business owners, and sanitation workers. At the same time, an SSP identifies all waste streams within a certain geographical boundary, say a specific peri-urban town. This can include the management of open storm water drains and the sewer system, solid waste collection and transfer, septic tank sludge collection and disposal, and agricultural uses of waste water. After all the parts and stakeholders of the sanitation system are identified, a comprehensive risk assessment and incremental improvement plan is agreed upon, monitored, and reviewed regularly.

You can find out more about how SSPs are implemented in practice in this article.

In the next step, Jan will be describing a peri-urban sanitation project in India and its challenges and achievements.

- Where, do you think, lies the biggest challenge in achieving universal access to improved sanitation in peri-urban environments of low and middle income countries?

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free